token slinging

17 years ago I discovered Google App Engine. It was the first truly scalable “serverless” platform that I had ever seen. I could just write an HTTP handler and it would scale to meet the demand.

It was also the first time in computing where I experienced a direct relationship with the cost of my code running. Prior to this every service I built was compartmentalized to a physical server. I was used to building software and algorithms for this model. Database contention, process contention, C10k, etc, were all things that I had to plan for. Yes, we developed your algorithms to avoid those problems, but we tended to scale by estimating the total QPS per box and when you hit a limit you would just buy another box and stick it in the rack.

App Engine however could scale to meet any demand I could throw at it. I just didn’t have to worry about any of the physical limitations or other constraints that I had previously worked with. It was a new world for me. I just had to deal with this one weird thing: A new billing model based on CPU time.

The more money that I could spend in the moment, the more access to CPU time I had. It was such an interesting model for me. What if I get popular? I’m just using this as a side-project… In the “old days”, my box would just grind to a halt and I would make a decision to either upgrade the box or buy another one. Now, what should I do? Should I charge my customers using a similar model? How would I explain that?

Ultimately, I chose not to follow that model for billing my customers. I felt that my customers would have no understanding of the model and would instead say “hey, it’s not our fault you use too many cycles to process a request”, and a normal per-month tiered SaaS model would be much easier. This model led me down a rabbit hole that I still reflect on a lot. My margin was the difference between a standard user and the compute it took to process their requests and this lead me down an optimization path that I never thought about before, but couldn’t get out of my head. CPU time cost me real money, so I need to reduce it on a per-user basis.

I did some back-of-the-envelope calculations and I realized that if I shaved off 100ms of CPU from my request handler, I would save tens of dollars a day (this was a lot for me at the time). I started to think about how I could optimize my code to get the CPU time down, lots of micro-optimizations here and there, and as I deployed each new version and I could see the CPU time drop.

I felt like an absolute genius. Then AppEngine changed their billing model…. hah.

Jump forward 17 years and I’m building software and using LLMs all the time to help me. They chew through bootstrapping of projects, bug fixes and even new features. I’m sold on the model and the gains that I personally get from it. Granted, I’m not a typical engineer; I’m a manager and I’ve spent a lot of time not building things over the last couple of years, but these tools have changed my life.

It feels like a real moment of change. “Normal Businesses” can be relatively rational when it comes to controlling costs, so my logical assumption is that if the companies are spending the money (and I’m hearing that they are), they have likely costed it out and they must feel that they are getting a return on investment. I hear from people in the wider-ecosystem that lots of companies have blanket deals with LLM providers to enable all of their employees to use LLMs all day, and when there isn’t a corporate deal, some companies give their teams budgets of a hundred dollars a day to use these tools.

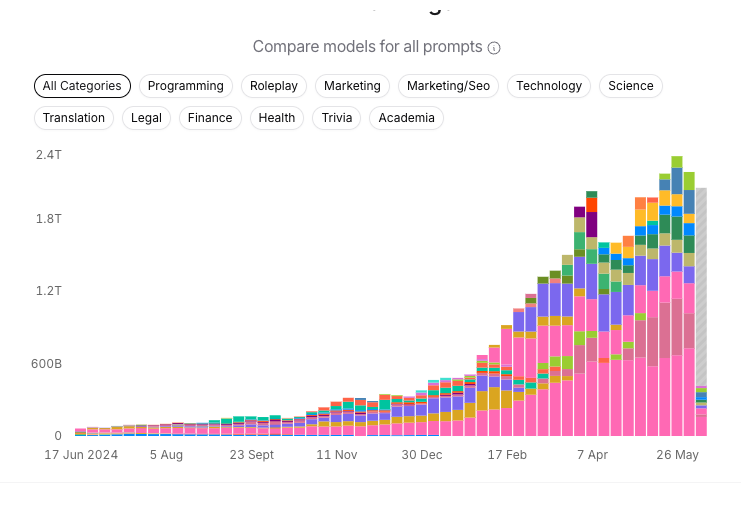

Inference trends seem to indicate that there is more usage happening. I find OpenRouter’s trends fascinating. They are a service that provides access to a wide range of LLMs, and they have been tracking the usage of these models across their platform. You can see the trends in usage, the most popular models, and even the top applications that are using these models.

OpenRouter Inference Trends

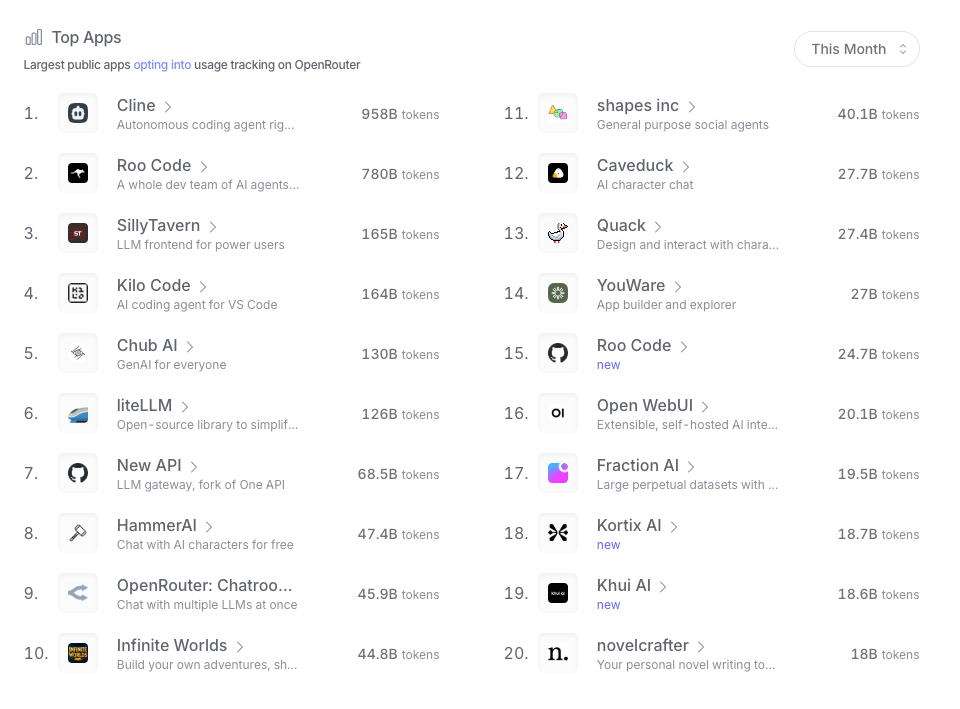

OpenRouter Inference Trends - Top Apps for the month

Looking at the numbers today (June 18th), 1 trillion tokens are processed by Open Router alone in a week and looking at programming, there’s at least 500 billion tokens processed in a week. And this is data from just one service. Mind blowing.

As LLMs chew through teraflops of compute, it seems like the token is the current best model for billing. When models are less intensive to run the tokens tend to be cheaper (Gemini Flash) and more expensive when they are doing more. Per token billing is the new CPU time billing.

It raises a number of questions for me as a web developer.

Firstly, for web developers selling a service that interfaces with an LLM how do you bill? Like CPU time, tokens just aren’t a measure that any normal person will understand, and they should probably never have to understand. We are going to see a lot of iteration in this space. For example, I run an RSS summary service called tldr.express. It’s small enough that I can eat the cost of running every RSS feed that is subscribed to through the LLM. But when I reach 1000 users, then what? I don’t think there is any way that I could add a margin on top of my direct token cost, I would have to think about a more traditional SaaS model and hope people use the service but not too much… Kinda like how I used to think about CPU time.

This per-token billing creates an incentive for service owners to move more of the processing on-device at the user’s expense. I’m not sure how I feel about this given the trade-off in terms of device capability and quality of today’s models. As web developers we will need more tools that will let us eval and balance the quality of on-device processing vs the cost and quality of using various services.

Today, there is a lot of experimentation by the model providers in pricing models, with Pro and Ultra plans. I could imagine a world where some of the current AI Web APIs (like Summarize or Prompt) doesn’t actually use the on-device model, but instead the browser recognizes that the user has a Pro account with a model provider and uses that to process the request. It’s still moving the token cost of the LLM from the site owner to the user, but it’s wrapped up in a more traditional billing model that the user understands. And with the added benefit that the results are higher quality because the models are significantly more capable than the on-device models.

Billing models for services aside, a bigger change that we are seeing is that for the first time in a long time the tools that we (Web Developers) use every day now have a cost associated tied directly with their usage and this is a huge change from the past.

I’m old enough to remember buying Visual C++ so that I could build Windows apps with MFC (I lied a bit here, my Dad bought it for me). Visual Studio with MSDN was my next main-stay for professional development. These tools cost real money, but it was either a very expensive one-time purchase or an annual subscription (anyone remember the mounds of MSDN CD’s?). Whether driven by Open Source, or tools coming in to the browser or just plain competition, Web Developers transitioned to expect that development environments and tool chains would be free (as in beer), or so low-cost that the price was negligible.

But this is changing in subtle ways. We are seeing an explosion of token-slinging services that cost significant amounts of cash. Cursor costs $20 a month for 500 requests (I think I get through 500 requests in a day sometimes.) Replit is per “checkpoint” and is now adapting to “effort” based billing — I find the effort-based billing particularly offensive because it assumes that they know they’ve completed a goal, and when the tool makes clear mistakes it’s incredibly frustrating. And then there are the purely token-processing tools like Cline and others. As I write this, there are now a number of CLI tools Gemini, Codex and Claude that are exploring being able to attach their tool directly to your consumer account (Ultra accounts get more requests than Pro, and so on).

This entire space is a difficult set of trade-off’s for web developers. You can feel incredibly productive and can see the output of it, and when things are going well, you don’t want to stop. But at some point, you have to pay or stop. So, what do you do? You can look at cheaper models, or you can think about going on-device as a way to satiate the cost. Are you really trading cost for quality, though? How can you even determine quality other than vibes? This was the only reason I switched to Gemini Pro. The code felt better but I didn’t have a real way of actually comparing it and I don’t believe any of the benchmarks.

I don’t know a single developer who today wants to produce a low-quality product or knowingly use a tool that outputs lower-quality code than another. Being able to determine this though is a real challenge and one that will increase as more developers find value in these tools.

Maybe this is just the same as picking a framework to use? You make a subjective decision in the guise of objective criteria: There are more developers, there are more libraries, my team will be more productive, etc etc.

I have a job that enables me to spend what I want to spend and see the benefits from it, but for a small individual developer or a small software shop, even $10 a day is a lot of money, and can equate to less than an hour of LLM usage so how should we think about our more junior folk or people starting out in the industry who don’t have access to the funds to use these tools?

How do we think about emerging or weaker economies? Tokens aren’t priced to the market they are being used in, they are attached to the dollar. If you’re in a region that has lower salaries, lower revenues or has a currency that isn’t as strong against the dollar, then you might struggle to be able to afford to use these tools even if the increase in productivity is significant.

We never did get out of the model that App Engine introduced. AWS just took it and made it number of requests and CPU time (GB seconds). Now, LLMs are doing the same thing but this time to the actual development costs and there might be an ever widening gap between those who can afford to use LLMs and those who can’t.

These are all very interesting problems that we as a web industry will need to solve.