headless stopgap

I remember my early days building for the web. We had no separation of concerns. We used <font> and <center> tags, transparent spacer.gifs, and complex table layouts to force our content into a shape. Presentation and content were a single, messy soup.

My first encounter with CSS in Netscape Navigator 4 was a mind-blowing moment. It was the first time I was confronted with the idea that you could (and should) separate the document’s structure (HTML) from its presentation (CSS).

This concept was cemented for the entire industry by the CSS Zen Garden. It was the ultimate demo: one single HTML file, hundreds of completely different visual designs. This idea, that content and presentation are two different things, has stuck with me ever since.

For the past decade, we’ve been running with this idea. Headless CMSs are the logical conclusion of that CSS Zen Garden-era thinking. We put our pure content in an API and make our presentation layer (a React app, usually) completely separate. We thought we’d finally achieved the ultimate separation.

But it’s a trap. We’ve just relocated the coupling. Instead of being locked to a WordPress template loop, we’re locked to contentful.getEntry() loops. We’re still manually mapping fields.heroTitle to <h1> and fields.heroImage.url to <img>. This isn’t freedom, it’s a 1:1 mapping to a rigid JSON schema instead of a flexible template.

Something has been gnawing away at me because I don’t think we’re at our final form of content management by a long way. As I explored in “Whither CMS?”, for years “normal people” and local businesses have fled to walled gardens like Facebook, not because they want to, but because the alternative is too hard. When I moved to North Wales, I saw this firsthand. They know their content, their goals, and their intent (name, address, pictures, booking forms), but the barriers of design, cost, and technical skills are too high.

That post also highlighted a key gap: the data shows popular CMSs (like WordPress) are dominant in the web’s massive “long tail,” but not where people actually spend their time. We’re still failing to provide tools for the vast majority of people who just want a simple, independent presence.

I do think with the introduction of Large Language Models we are on the verge of the next great separation. The first was (Content + Style) -> (Content) + (Style) with CSS and CMS systems. The new one is (Rigid Components) -> (Pure Intent) that will enable us to move from “structured data” to “intent.”

It seems that LLMs will finally make this possible by acting as the bridge, allowing anyone to simply describe what they want, starting with their content (the most important part) and progressively layering on style and functionality.

The “block editor” (Gutenberg, Notion, etc.) was a step in the right direction, but it’s still a “what you see is what you get” system that mashes content and presentation into a messy HTML blob. You can’t easily change the markup of every “Two Column” block on your site.

The new model requires a hard separation of “Content” and “Chrome.”

- Content: The text, the image URL, the list items. This is sacred and must not be changed by the LLM. In my experimental ssgen project, this is just raw Markdown.

- Chrome: The

<div>s, thegrid, theshadow-lg, therounded-xl. This is the shell that presents the content. It is disposable and should be generated.

The LLM’s role is to act as a just-in-time “chrome generator.” It reads the pure content (# My Title) and wraps it in the appropriate presentation (<div class="hero"><h1 class="text-4xl...">My Title</h1></div>) based on context, leaving the content itself pristine.

Right now, we ask people to style with tailwind.config.js, _variables.css, and create massive design system libraries. A new model could be “Intent.” Instead of coding the style and the intent, we describe it. The LLM acts as the style-transfer engine.

My ssgen experiment shows that this is possible in three ways:

- Textual Intent (The Brand File): We give the LLM a simple “brand.md” file. “Our brand is professional and minimalist. Use a dark blue primary color (#0a2351), a serious serif font for headings, and generous white space.”

- Visual Intent (The Screenshot): We give the LLM an image. “Make it look like this.”

- Functional Intent: Describe what you need to do and hypermedia can make it possible.

The LLM uses this “intent” to inform how it builds the “chrome”, enabling us to bridge the gap between the author and the final code.

But how can we think about describing intent while enabling ease of authorship? One of the things that I loved about HTML was its ability to render even if the input HTML was malformed in some way. No </p>, not a problem. What if we could extend that flexibility even further into describing what you want?

If as an author I could describe that I want a <contact-form> and what I want it to achieve even if I don’t know HTML, that could be pretty powerful.

Maybe I could write something like this:

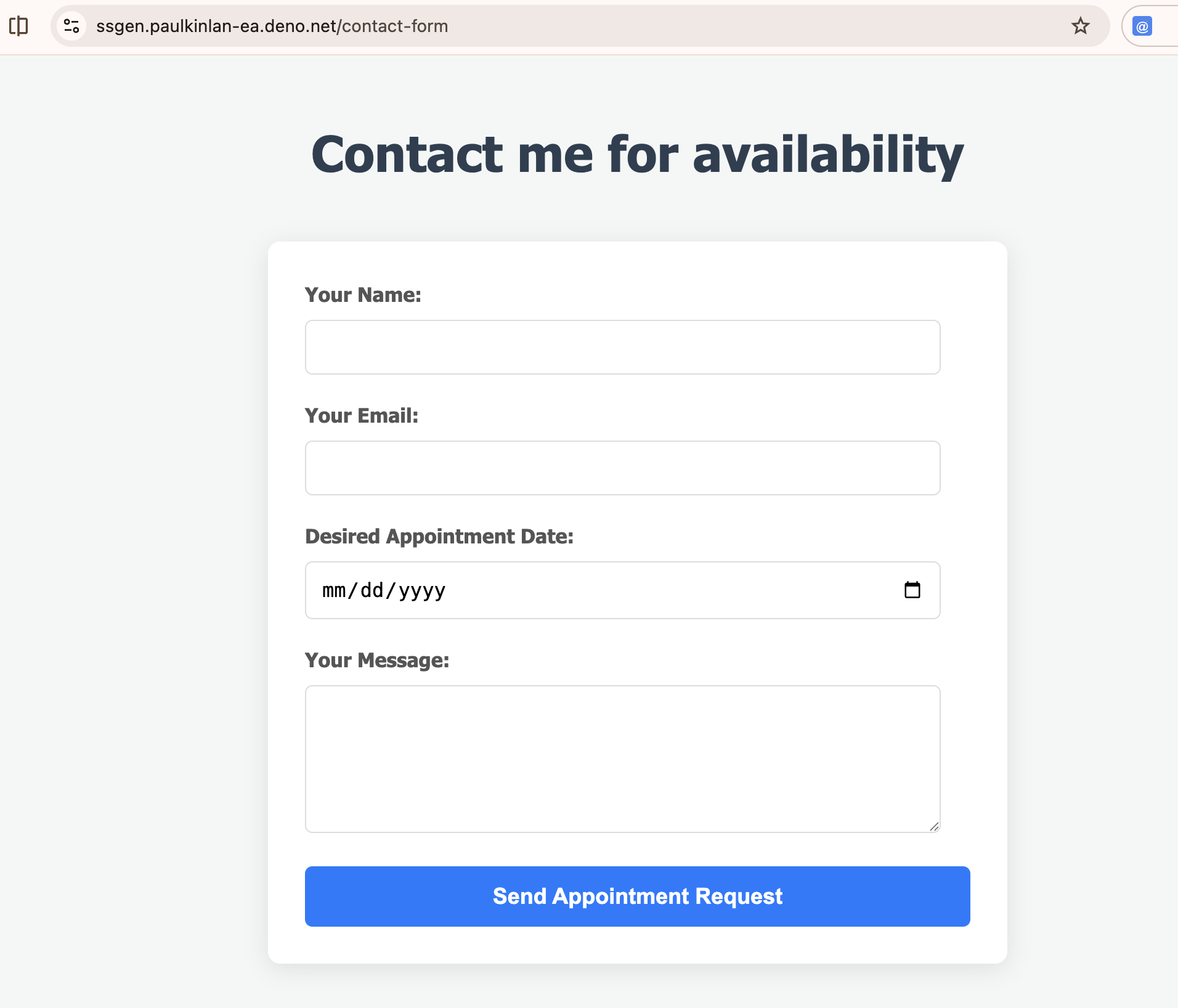

# Contact me for availability

<contact-form>

mail to: paul@aifoc.us

I need the users name, email address, message and date they would like an appointment

</contact-form>

Should produce something like:

ssgen‘ed form

Oh - wait it does | Code.

This brings us to what I think is the most powerful idea. Back in 2016, I wrote a post called “Custom Elements: an ecosystem. Still being worked out.” The dream was that semantic, custom HTML elements could become a universal interchange format. An author should be able to write <share-button> or <aspect-image>, and the developer or platform would provide the best implementation for that context (whether it was Polymer, AMP, or just vanilla JS). The author’s HTML would be stable, even if the underlying tech changed.

Yes, that future did not happen, but as the post warned, framework ecosystems exploded, and each one built its own proprietary, prefixed component model (<amp-img>, <iron-image>). This fragmented the composability of the platform. We didn’t get an ecosystem; we got a set of high-walled gardens that locked developers in. A React <ProductCard> is almost useless in a Vue app. However, if you look at how people use frameworks like React, <ProductCard> and <ContactForm> are surprisingly good, descriptive definitions of the intent of what is being created.

Can we use LLMs to finally deliver on that original vision of semantic, functional HTML elements that are implementation agnostic?

I think there’s a massive opportunity to cement the web as the place for all content and I think the LLM is the missing piece that can finally deliver on the concept I set out in 2016 to bind an implementation to an author’s intent.

Consider the two roles:

- The Author’s Job: Write pure semantic intent.

- The LLM’s Job: Act as the “intelligent renderer” (e.g,

ssgen). It sees these tags, understands their function and contract, and generates the entire, correct, and secure implementation (the<iframe>, the<form>, the Stripe.js<script>) on the fly, using the brand guidelines.

I think this is decoupling that we should explore more. Authors don’t need to know HTML, JavaScript, or even what framework is being used. They just declare their high-level intent, and the LLM handles the implementation, which might help us to break the framework lock-in for good.

Consider this example of functional elements that ssgen can already generate:

---

prompt: element.md

---

This is a test page testing how elements being automatically generated.

# Google Map and Pin

<google-map><pin-location city="Ruthin"/></google-map>

# Google Font

<google-font font=Lobster size=30pt>Hello World</google-font>

Google Map and Google fonts generated by LLM

Demo: View Element Demo Code: View on GitHub

These elements were entirely made up as a way to explain what I wanted in the page. The LLM understood the intent of what I wanted and generated the correct code to make it happen.

I could imagine a world where you could write:

Welcome to my site about travel! Here is my trip to the tower of London:

<google-map location="Tower of London" zoom="14" />

You can book tickets using here:

<checkout-button item="prod_123xyz" price="19.99" currency="GBP" />

If you want more information about my travels, sign up to my newsletter:

<newsletter-signup form-id="my-campaign-id" />

I think this is pretty fun. Exploring this model further, we can create more complex elements.

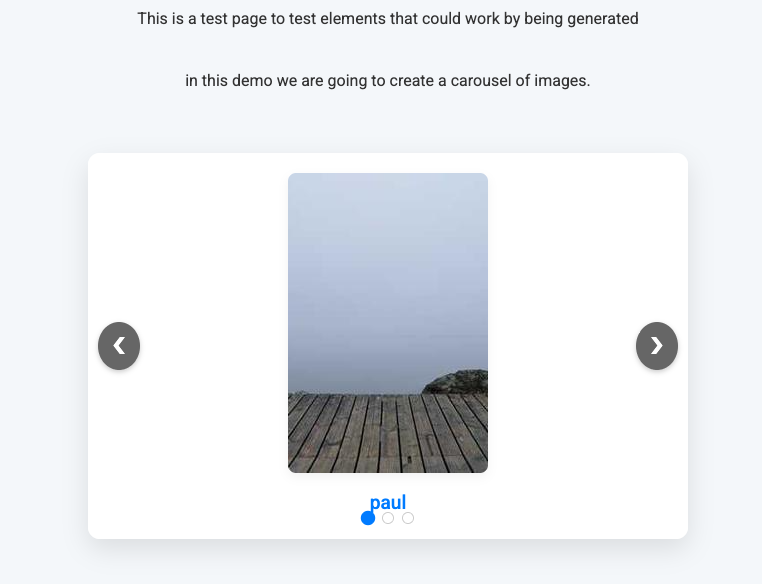

How about a carousel of images?

---

prompt: element.md

---

This is a test page to test elements that could work by being generated

in this demo we are going to create a carousel of images.

<carousel>

Img url=https://picsum.photos/200/300 link_text=paul kinlan link=https://paul.kinlan.me

Img url=https://picsum.photos/200/300 link_text=web dev link=https://web.dev

Img url=https://picsum.photos/200/300 link=https://developer.chrome.com link_text="chrome." ; open the link in a new window

</carousel>

Carousel generated by LLM

Demo: View Carousel Demo Code: View on GitHub

The LLM understood the intent of what I wanted and generated a working carousel with navigation buttons, image links, and accessibility features.

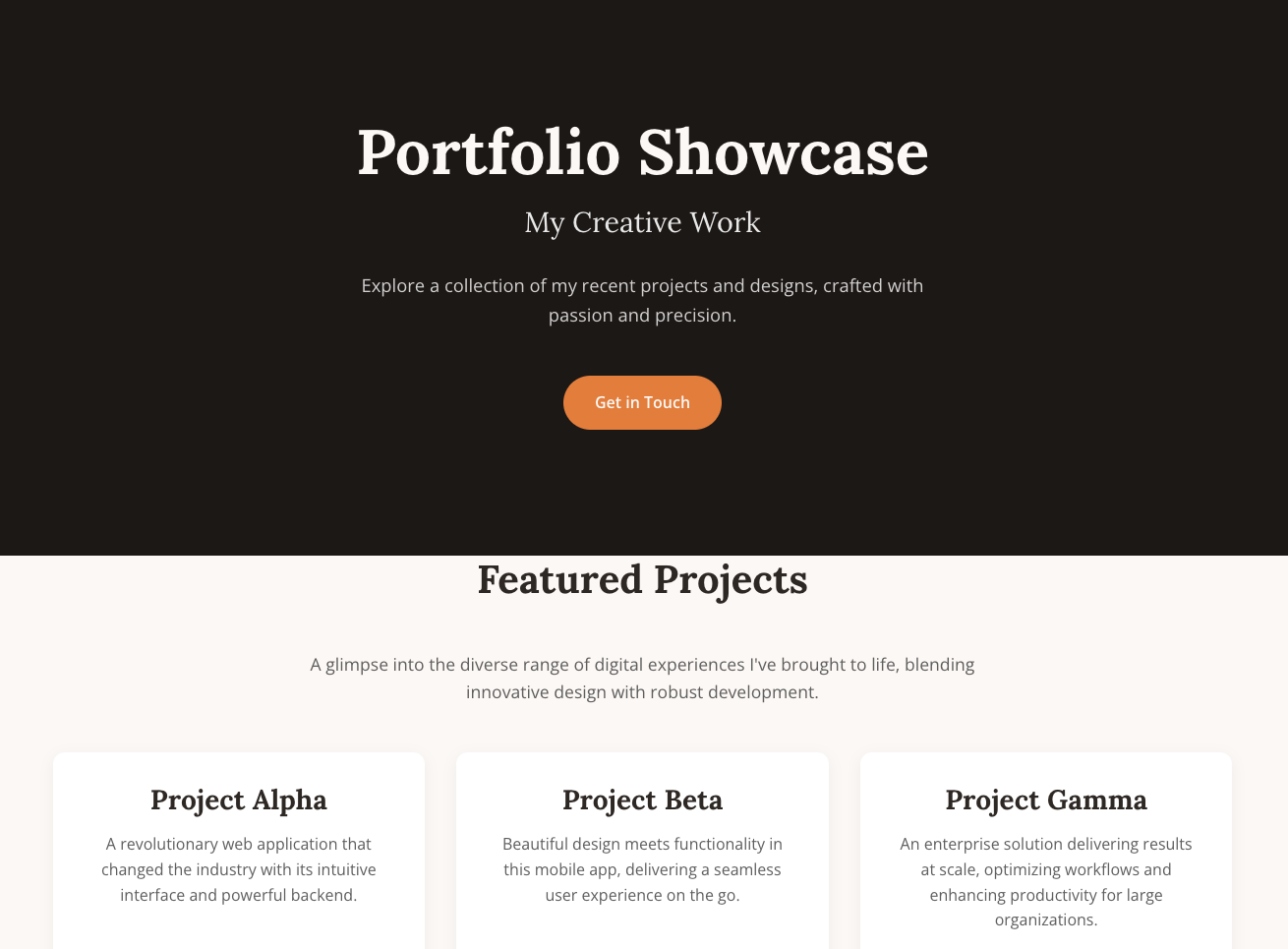

Finally, consider a full portfolio page where I provide the content and a screenshot of the style I want:

---

prompt: element.md

style:

image: images/screen.png

---

# Portfolio Showcase

## My Creative Work

Explore a collection of my recent projects and designs.

## Featured Projects

### Project Alpha

A revolutionary web application that changed the industry.

### Project Beta

Beautiful design meets functionality in this mobile app.

### Project Gamma

Enterprise solution delivering results at scale.

## About Me

I'm a designer and developer passionate about creating beautiful, functional digital experiences.

## Contact

Let's work together on your next project!

Demo: View Style Transfer Demo Code: View on GitHub

Site generated by LLM with image as source

As more and more people get used engaging with LLMs, I think we can start to see a new model for content management and site generation emerge.

The new workflow is simple:

- You write semantic content (Markdown + custom functional tags).

- You provide stylistic intent (a brand file or a screenshot, or even CSS file).

- An LLM Renderer (

ssgen!) generates the complete, functional, and on-brand site.

I like the idea that a CMS can become a simple text file (Markdown) that anyone can write, and the “renderer” is an LLM-powered engine that can understand both the content and the intent of the author.

There are a number of challenges that I can see you already raise:

The first two (latency and deterministic output) are hard-stops for many if you think about how today’s web is built to ensure that the experience works the same across all browsers and devices for all users. Latency is starting to be solved. The non-determinism through? This might actually be a feature.

If we embrace this non-determinism, we are now in a world where every navigation to a page is an opportunity to generate the best possible experience for that specific user, on their specific device, for their specific browser, no matter their context.

By understanding the user’s context, we can also be a lot more progressive. Progressive enhancement starts with a functional baseline and adds features based on the browser’s capabilities. By sending the HTTP headers on the request through to the LLM, we can influence the output of the LLM to produce code that is the best possible experience for the browser (e.g., Chrome, Safari or Firefox) and the platform (e.g., desktop or mobile). This makes API documentation and best practices even more important and critical to be in the model’s training data or the tool’s context. As we’ve seen with Progressive Enhancement, it’s still a hurdle to get businesses over that the site doesn’t work exactly the same everywhere.

The real big challenge that I see is: Security and the validation of the intent. How do we ensure that the generated code is safe, secure, and does not expose vulnerabilities? We need to build robust “element handlers” that can validate and sanitize the generated code before it goes live, or even force the pages to run in highly sandboxed and CSP-restricted environments. CSS is (in my eyes) the correct layering for the technology that is HTML. It got us out of spacer.gif hell and allowed us to separate content from presentation.

Headless CMSs were a step in the right direction because they made content management more flexible, but they are just a stopgap. The real future is about separating content from presentation and functionality at a higher level of abstraction using the user’s language, and using LLMs to generate the “chrome” based on the author’s intent and if we follow this model I think we can get people out of the vendor lock-in that we see with prescriptive frameworks and platforms and make the web the best and easiest place for everyone to publish their content.