If NotebookLM was a web browser

NotebookLM is one of my favorite applications in decades. If you haven’t experienced it before, it’s an application that lets you pull in sources from all around - Google Drive, PDFs, public links - collate them into a notebook, and then query or transform that content. Want to turn five research papers into a podcast? Done. Need to extract key takeaways from a collection of articles? Easy. It’s a fundamentally different way of interacting with information that wasn’t possible before large language models.

But there’s something that has been nagging at me. The browser already is a collection of sources. Tabs, bookmarks, history, tab groups, links in the page - these are all repositories of content that I’ve deemed interesting enough to keep around or could be interesting enough to explore. Yet the ability to manipulate what’s across those sources isn’t something we’ve spent much time thinking about, our traditgional model of browsing is still very much “one page at a time.”

What would happen if NotebookLM was actually a web browser?

One of the things I love about browsers and the web is that the browser is my user agent for my viewing the entirety of the web. It has full access to the content I consume. Chrome extensions can come in and augment pages, provide extra functionality the original author didn’t plan for. The pliability of hypertext, that is: HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, means we can reshape content to suit our own personal needs. I’ve been thinking a lot about hypermedia and the original visions from pioneers like Vannevar Bush and Ted Nelson, where users would create their own links and trails through information. The web gave us the <a> tag, but the link as we know it is still fundamentally author-controlled and static. We haven’t really taken this to its logical conclusion. If I have fifteen tabs open about the same topic, why can’t I query across all of them? If I’ve bookmarked a collection of articles over the past year, why can’t I transform them into a study guide? The data is right there, inside my browser.

So I started to explore this in an experiment that I call FolioLM. Consider a scenario: I find an interesting thread on Techmeme with fifteen different news sources covering the same story. Today, I’d have to open each one, read through them, and manually synthesize. With FolioLM, I can select all those links, add them to a folio, and ask “What are the key differences in how each outlet is covering this story?” Or transform them into a comparison table. Or a timeline of how the story evolved. This isn’t just convenience. It’s a fundamentally different relationship with information. The browser becomes less of a window and more of a workshop.

Here’s something that differentiates FolioLM from NotebookLM and similar tools: it runs inside your browser, which means it has access to everything you have access to. That paywall-protected article from the Financial Times? If you’re logged in, FolioLM can extract it. That internal wiki behind your corporate firewall? Accessible. That research paper you can only read because your university has a subscription? It’s right there.

External tools can only see what’s publicly available on the open web. But the browser is your authenticated view of the internet. It carries your cookies, your sessions, your credentials. When you extend the browser with something like a Chrome extension, that extension inherits that same authenticated context. The content that matters most to me - the stuff I’m paying for, the stuff behind logins, the internal documentation - is exactly the content I most want to query and transform. And because FolioLM operates within the browser, it can.

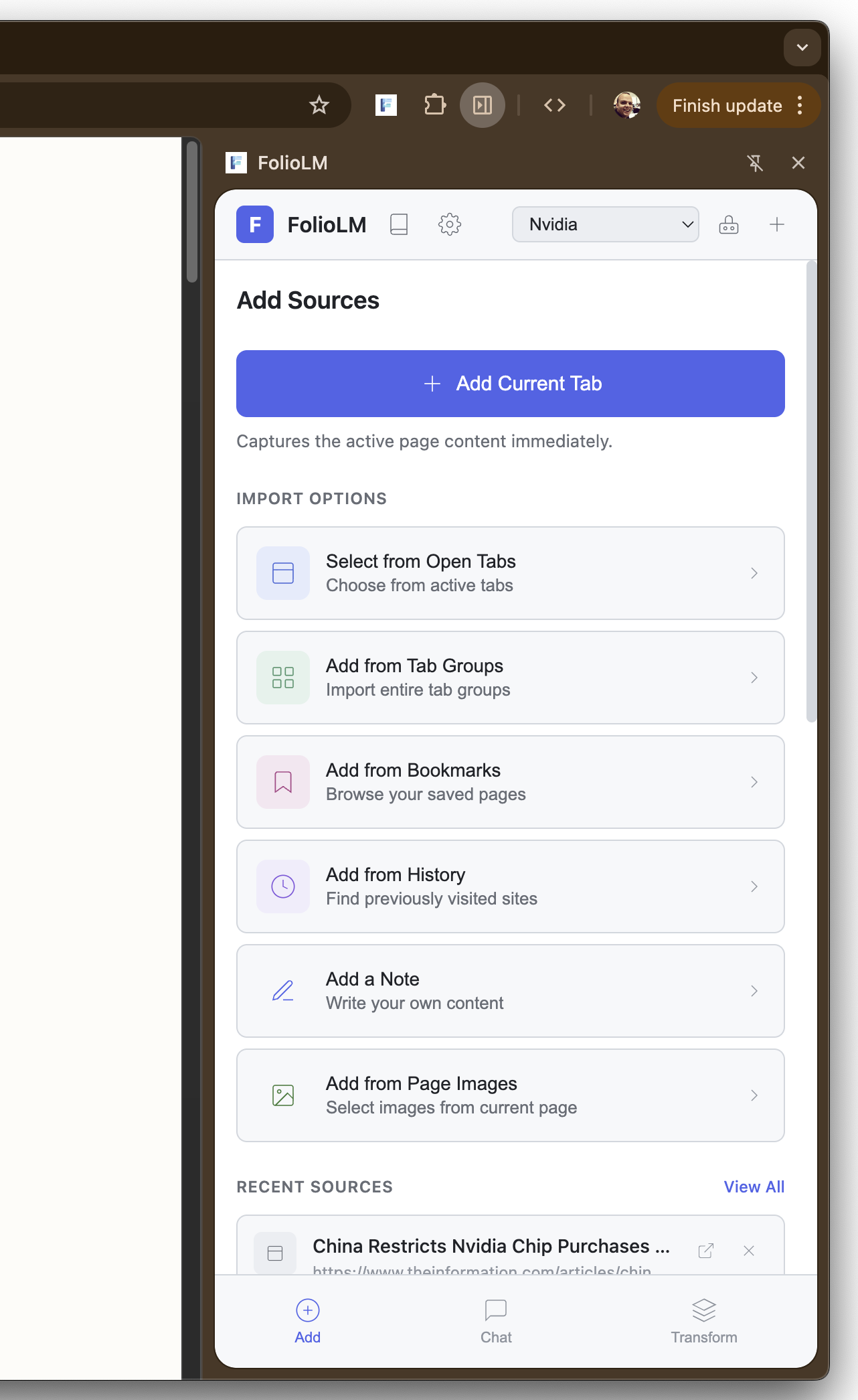

FolioLM is a Chrome extension that tries to bring NotebookLM-style capabilities directly into the browser. You can add sources from anywhere the browser can see: the current tab with one click, multiple selected tabs at once, all tabs in a tab group, bookmarks, browser history, right-click any link or image, drag and drop links from web pages, or create your own text notes.

Adding sources from tabs, bookmarks, and history

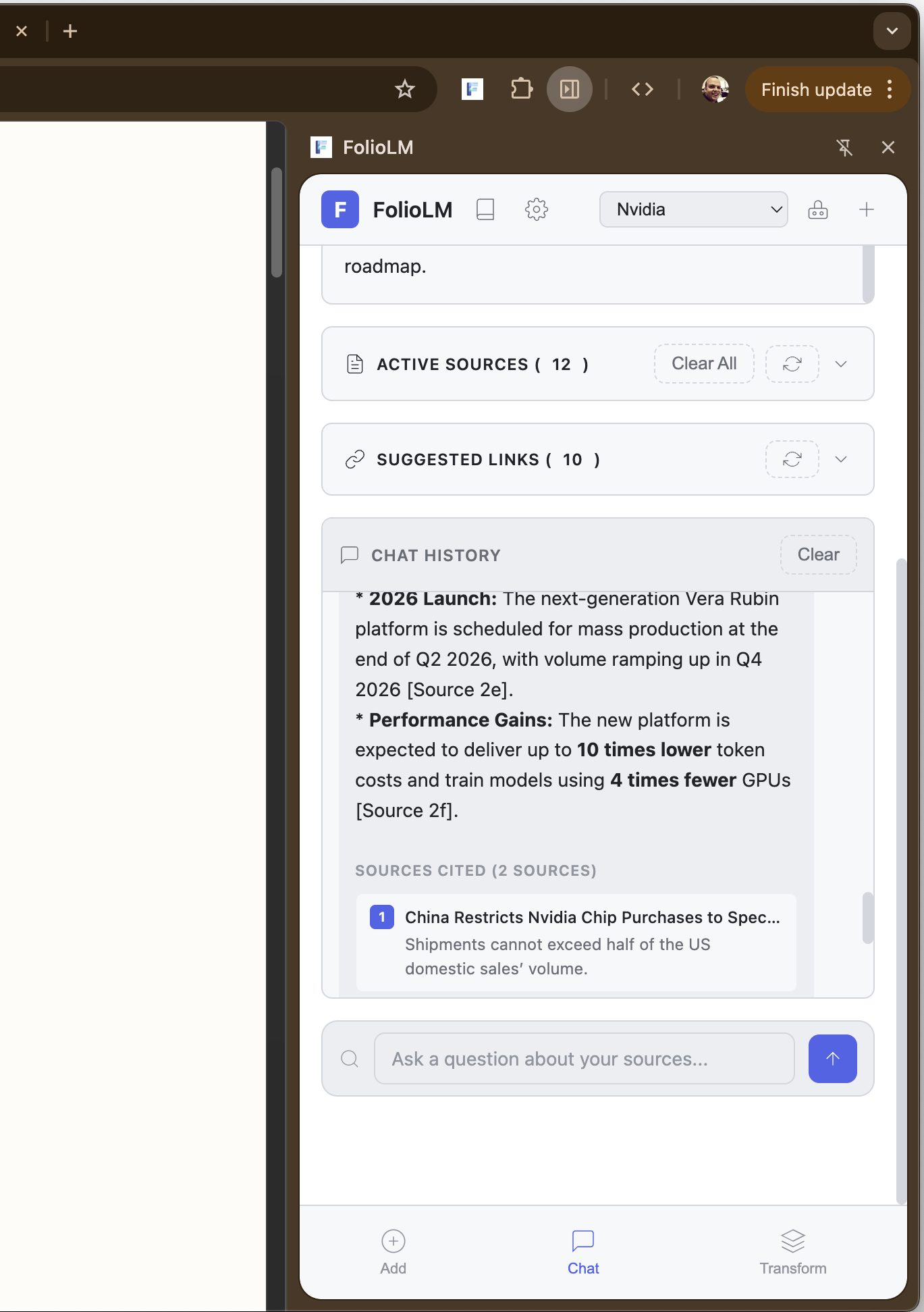

When you add a source, FolioLM extracts the content and converts it to clean markdown using Turndown, filtering out navigation, ads, and boilerplate. You can then query across all your sources with natural language, getting answers with citations back to the original sources. Clicking a citation opens the source URL with text fragment highlighting, so you can see exactly where the information came from.

Querying sources with AI-powered chat and inline citations

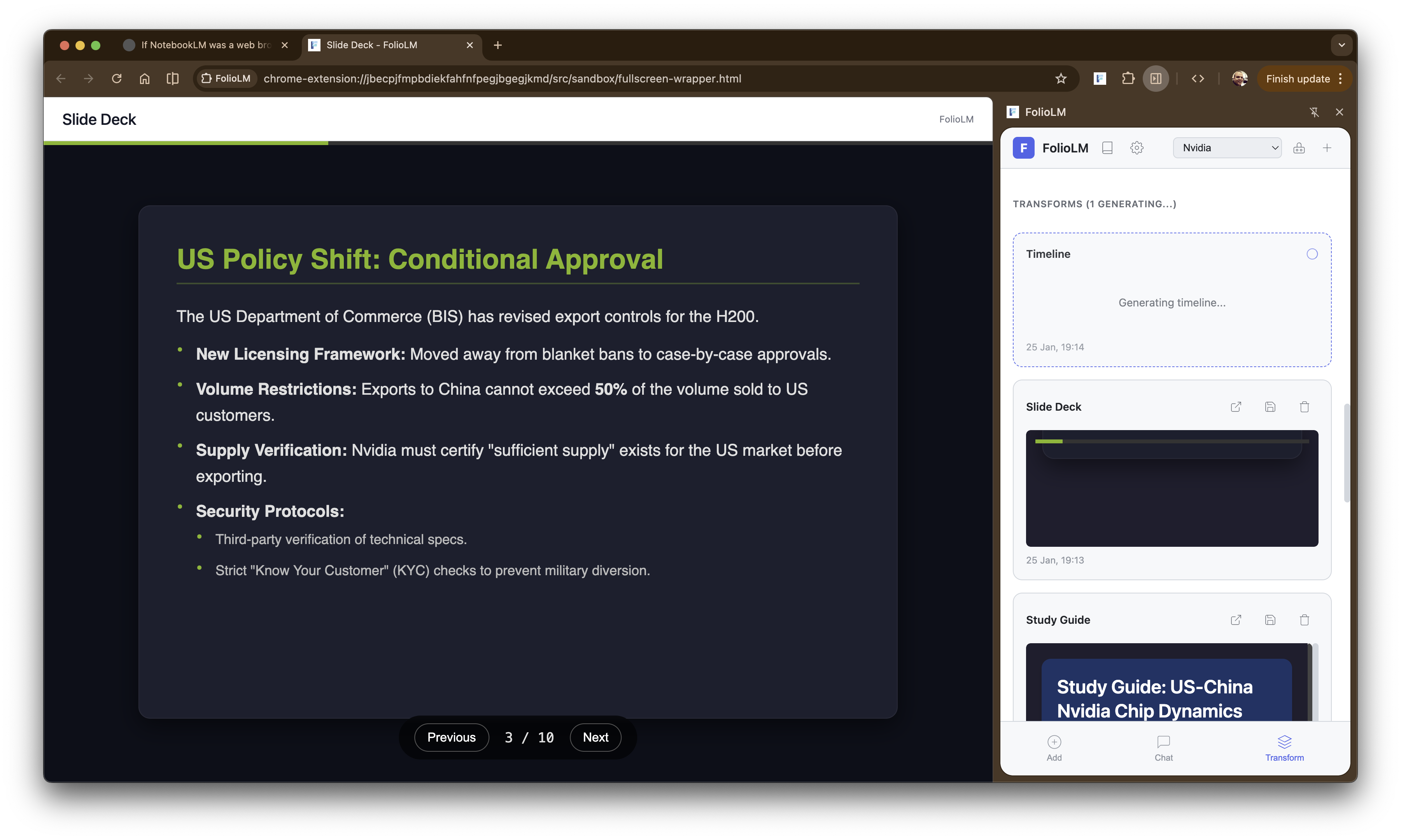

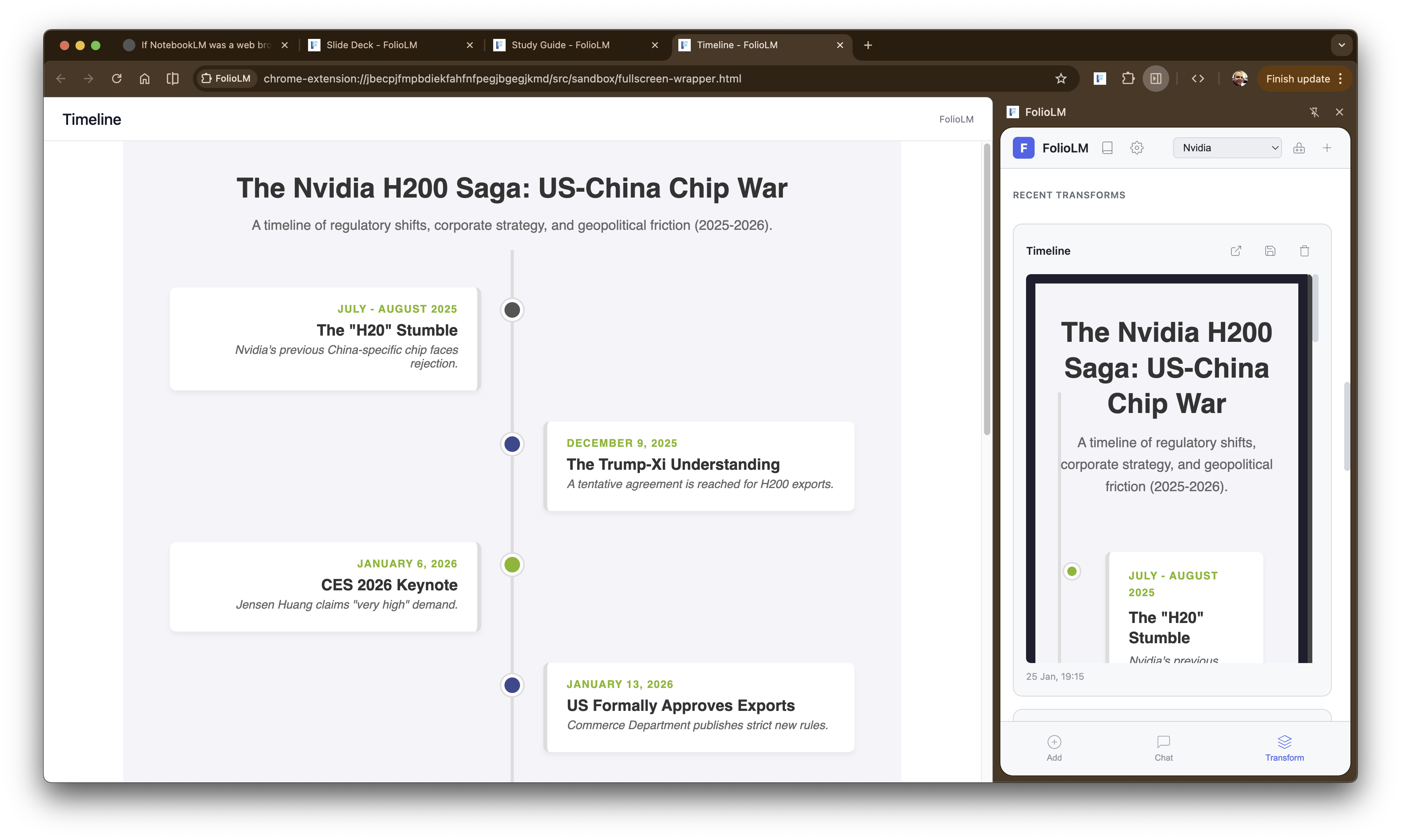

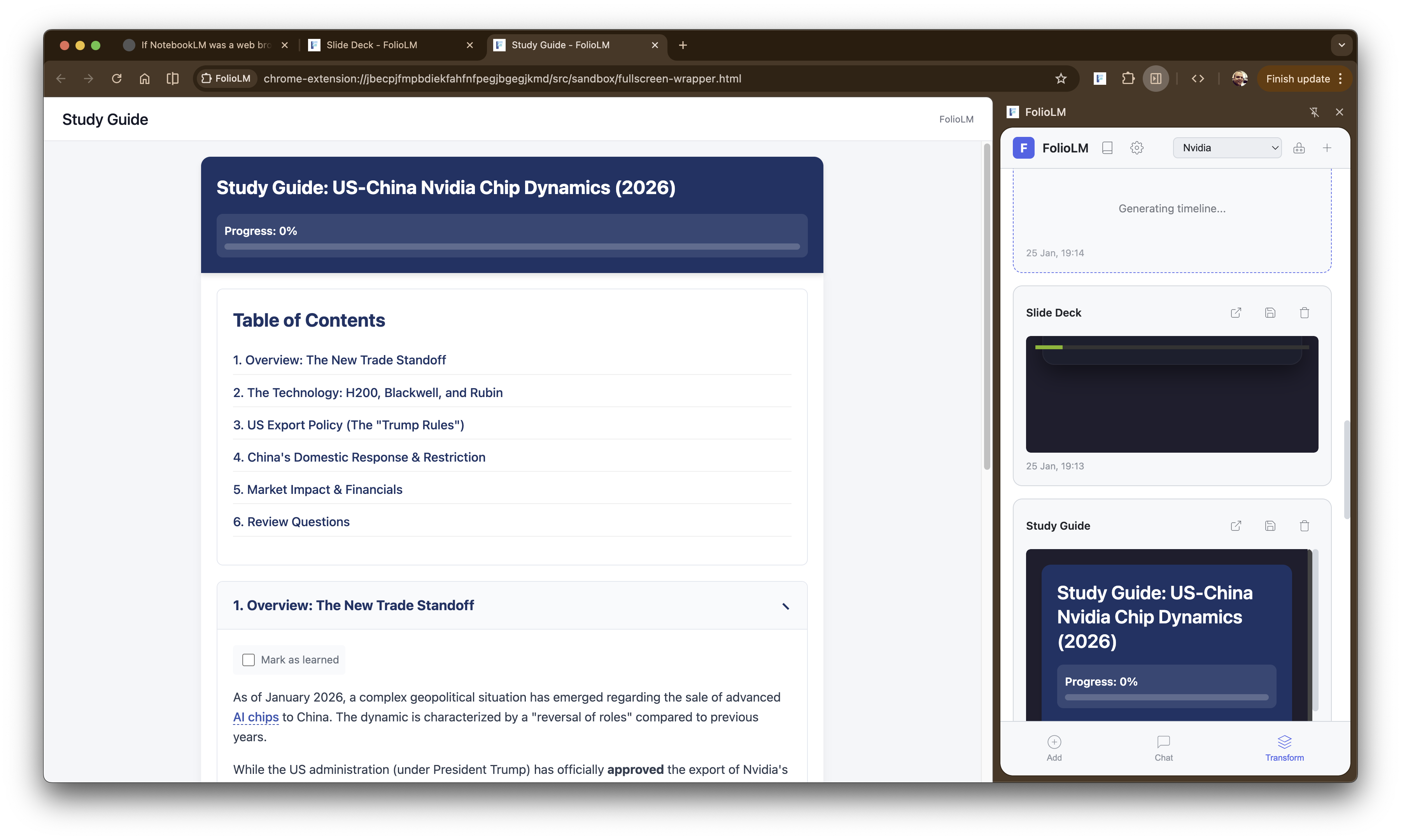

The transformations are where it gets interesting. I’ve been exploring hyper-content-negotiation and the idea that content on the web could be served in whatever format the user wants. FolioLM takes this a step further by letting you transform content you’ve already collected. It can transform your sources into 19 different formats: quizzes, flashcards, study guides, podcast scripts, email summaries, slide decks, reports, timelines, comparisons, data tables, mind maps, glossaries, FAQs, outlines, citations, action items, executive briefs, key takeaways, and pros/cons analyses. Each is configurable - you can adjust the number of quiz questions, the tone of the podcast, the depth of the report. The results can be saved, opened in full-screen, or copied to your clipboard.

Transforming sources into a slide deck presentation

Generating a timeline from collected sources

Creating an interactive study guide

On the technical side, it’s a Manifest V3 Chrome extension built with TypeScript, Preact, and the Vercel AI SDK. It supports 16+ AI providers including Anthropic, OpenAI, Google Gemini, Groq, Mistral, and Chrome’s built-in Gemini Nano (which works offline and costs nothing although can’t process anywhere near as much data). Transformations run in the service worker, which means they continue even if you close the side panel.

I grew up with the Web and it’s incredibly important to me, specifically the link. I tied to build this tool to enhance my relationship with web content, not replace it. Every source keeps its original URL with an external link icon that opens the original page in a new tab. When the AI cites a source, those citations are clickable (they open the source URL with text fragment highlighting), so you land directly on the relevant passage (there are bugs, sometimes it doesn’t quite work).

The extension also extracts links from the content itself. When you add an article, FolioLM captures all the outbound links along with their anchor text and surrounding context. These get analyzed by AI and surfaced as “Suggested Links” which are related sources you might want to add to your notebook. It’s important to me to encourage myself (and anyone who uses the tool) to explore more of the web, not less. Source types are visually distinguished with icons so you always know where content came from. Nothing is locked inside the extension; every piece of information has a path back to where it came from.

This matters because it would be easy to build a tool that just ingests content and presents it in a closed environment. But that’s not the web to me, it’s useful, but exploring the web is what I love.

There’s a pattern I keep coming back to: the browser knows things about my browsing that I don’t fully leverage. It knows what tabs I have open, what I’ve bookmarked, my history. But these remain largely isolated data stores. When I think about the intersection of AI and the browser, I see an opportunity to make the browser a more intelligent user agent that is active in how I consume and synthesize information.

This connects to a broader question I’ve been wrestling with. In super-apps I wrote about how LLMs like Gemini and ChatGPT become the everything-app then you will rarely need to leave them. If that’s where things are heading, what happens to the web? In interception I experimented with having LLMs intercept and transform every web request. In embedding I explored how the web needs better primitives for composability if it’s going to remain relevant.

There’s a tension here that I’ve been thinking about for a long time. When we were launching the first version of the Chrome Web Store in the early 2010s, I worked with magazine and digital publishers to bring rich, high-quality content experiences to the web. Many of these publishers had been successful on the iPad, and we wanted that same quality on the web. But we kept hitting the same wall: nearly every publisher wanted their layout, their text, their images to render exactly as the editor intended. Pixel-perfect. And we’d have to explain that the web doesn’t really work that way. You can resize the browser. You can zoom. The content reflows. People can change the page with Chrome Extensions and Grease Monkey scripts. The publishers hated it. They’d been promised by that the iPad would maintain the exact vision of the editor, and they wanted that same guarantee on the web.

That disconnect has stuck with me. I think many publishers still want complete control of their experience. And as users, we want to be able to transform those experiences to make them more useful for us. Chrome Extensions already cause tension when they manipulate sites on the user’s behalf. I’m honestly not sure whether some of my more aggressive experiments - like interception where LLMs rewrite entire pages - will ever be broadly acceptable.

Which brings me back to why FolioLM takes the approach it does. It’s not rewriting pages or intercepting content. It’s a companion (a coworker if you will, heh!) for information management that generates complementary experiences personalized for you, leaving the original content intact. I’m not trying to replace the browser or become a closed super-app, I’m trying to make the browser itself more capable and to give myself tools to work with web content. The web has always been about connecting documents with links being the fundamental unit of the web’s structure. But we’ve mostly treated that structure as something staticm, that is you follow a link, you read a document, you maybe link to it in your own writing. What if the browser could help you see patterns across documents? Synthesize information? Transform it into new forms? I’d personally flippin’ love that.

That’s the question I’m exploring with this site, FolioLM, and many other experiments. I built almost all of FolioLM with coding LLMs and my voice. Very little handwritten code. This is the intersection I find most exciting right now: LLMs can help you synthesize information across browser tabs in ways we’ve never been able to do before, and LLMs can help you build the tools to do that synthesis in the first place. We’re getting closer to a point where you don’t need a team or a company to build something like NotebookLM. If you want an information management tool that works the way you work, you can build it. FolioLM is my tool, built for me, that works the way I want it to work. It doesn’t need to be a polished product with onboarding flows and pricing tiers. It just needs to solve my problem. And if it solves yours too, great. If not, maybe you build your own.

The browser is the runtime. The web is the data source. LLMs are both the capability layer and the means of construction.

If you want to try it out or fork it for your own purposes, FolioLM is available on GitHub. Also, a big thanks to Joseph Mearman who loved the idea of this and hopped in and also started adding to it :D