the browser is the sandbox

I got hooked on Claude Code over the holiday break and used it to create a number of small projects in record time. The CLI works well, and claude.ai/code has a really nice way of just firing off tasks and then reviewing them when done. The model has enabled me to create and ship a lot of personal projects that I’ve always wanted to build (I will talk about my process in a later post, as I think software development is changing very quickly with CLIs like Gemini and Claude). For example, I created a Chrome Extension that works like NotebookLM but uses your active Tab as the source material, and another that transcribes and transforms my voice to insert directly into text boxes. This efficiency allowed me to rip through a backlog of ideas.

I then saw Claude Cowork and thought that if it makes it easier for people to perform tasks that work across some of the files on your device, then it could be a pretty compelling view of the future of automation for non-coding computing tasks. One of the worries that people rightly have is giving unfettered access to a tool that you don’t know how it works and can perform destructive actions on your data. My use of agentic loops (CLIs in particular) has always worried me a little, as I tend to be a bit risky and run tasks without constraining the tool’s access to my file system. While I feel in control because I monitor the interactions, I know I’m taking a risk. If these new agentic-use patterns are found to be valuable by regular people, we have to ensure that tools can’t run riot on a user’s machine, either by accessing things they shouldn’t or modifying things without permission.

I read a post by Simon Willison that described how Anthropic implemented this using their sandbox experiment to create a sandboxed VM that is locked down to only the directory that the user selected with limited network access.

This got me thinking about the browser. Over the last 30 years, we have built a sandbox specifically designed to run incredibly hostile, untrusted code from anywhere on the web, the instant a user taps a URL. I think it’s incredible that we have this way to run code that you’ve no clue what it will do when you see a little blue link or a piece of text that looks like https://paul.kinlan.me/ - I mean, who would trust that guy?

Could you build something like Cowork in the browser? Maybe. To find out, I built a demo called Co-do that tests this hypothesis. In this post I want to discuss the research I’ve done to see how far we can get, and determine if the browser’s ability to run untrusted code is useful (and good enough) for enabling software to do more for us directly on our computer.

The sandboxing framework

I liked Anthropic’s README for the sandbox experiment and it’s a good place to start:

Both filesystem and network isolation are required for effective sandboxing. Without file isolation, a compromised process could exfiltrate SSH keys or other sensitive files. Without network isolation, a process could escape the sandbox and gain unrestricted network access.

We have some ability to control these inside the browser. I can see at least three areas of sandboxing that we need to examine:

- The file system - you don’t want an autonomous system to be able to change files without permission, or reach out past where the user has given access. You also probably want some sort of backup.

- The network - you don’t want the system making requests to sites and services with your data (either generated data or actual file system data). There are plenty of ways to exfiltrate data.

- The execution environment - you are running code that someone somewhere has created (similar to

sandbox-execon macOS).

Let’s examine each of these.

The file system

I think the browser has built up a good model of protecting the user’s file system from unwanted access while also giving people control. We can access the filesystem through a number of different layers:

- Layer 1: Read-only access -

<input type="file" webkitdirectory>will let the user select a folder and you can then read the files that are in those folders. - Layer 2: Origin-private filesystem - while not directly giving access to the raw filesystem, you get the ability to have a filesystem directly in the browser only accessible to the current origin.

- Layer 3: Full access to a folder - Building on top of Layer 1, you can get a handle directly to the user-selected folder via the File System Access API. With permission, you can both read and write to it, but you can’t access any level higher in the directory tree or look at sibling directories. Effectively, you have a

chroot-like environment restricted to that specific handle.

I think this is pretty compelling. You could imagine a Layer 1 and Layer 2 solution working together: a web application could read the data the user has granted access to and then save some edits to a file on the Origin, keeping the original file intact and letting you continue edits.

Layer 3 is where it gets interesting (and scary). Being able to edit files enables so many new use-cases and possibilities for automation and knowledge-work, but we have to put complete trust in the browser’s runtime to ensure that sites can’t break out of this filesystem jail.

One area that demands caution: running code or HTML from an untrusted source, like an LLM, could extract content from the page to exfiltrate elsewhere, edit or delete critical content you’ve granted access to, or create malicious files intended to run later (e.g., adding a .doc file with a macro).

The network

So if we are able to access selected directories and all the files within them on a user’s machine, how do we ensure that the data remains within our control? We have to be able to completely control the network.

The blunt answer is that unless you have an entirely client-side LLM, you can’t. You have to send the data in your files, or a list of your files, at some point for the LLM to do work on them. The best that I think we can do is “manage the network”.

Normally, Content Security Policy (CSP) is the bane of a web developer’s life, but here it is our friend. Unlike a VM, which can strictly control the network interface of the host OS, the browser doesn’t offer that level of total isolation. But via CSP, we do have some control.

Why is this important? There are lots of ways to craft URLs such that you can pass data that the user thought was private into another system without any intervention from the user. For example, displaying an image in the browser is an expected thing on the web. You could ask an LLM to generate an <img> whose URL contains some sensitive data from the file, which will then happily be sent to the server “hosting the image”.

CSP can protect us somewhat. We can set a pretty strict CSP constraint on the origin so that the only network requests that can be made are to self and to a set of developer-configured origins (such as an LLM provider). This means that the host page can also set constraints to stop image, media, object, and font loading. However, manually configuring these can be error-prone, so it is safer to start with the most restrictive policy (default-src 'none') and then selectively open up access to the specific services you require. But even then, we are putting our trust that the LLM provider doesn’t provide open access to other GET requests.

Sandboxing LLM output

If we display any content from the LLM, we should also heavily sanitise the data. Actually, we should probably completely sandbox it. <iframe>s are a great way to separate content as they can create a layer of indirection from the host and things we want embedded; however, as we will discover, they need some improving to be valuable for our sandboxing needs.

A game-changing feature is the sandbox attribute on the <iframe>. It allows us to further isolate generated content from the main page by placing the frame into a ’locked-down’ mode where it can do almost nothing. It can’t run JS, it can’t navigate, etc., unless the host page allows it. This restrict-then-include model stands in contrast to the allow attribute (Permissions Policy), which controls access to advanced APIs. For example, your allow attribute might become: allow="camera 'none'; microphone 'none'; geolocation 'none'; fullscreen 'none'; display-capture 'none'; payment 'none'; autoplay 'none'"

This looks like a good model: we can restrict the ability to run dangerous JS and further remove access to powerful APIs. But if an LLM can be coerced to generate an iframe element, then it might be possible to escape the sandbox because, surprisingly, the host page’s CSP doesn’t filter into the iframe unless you use srcDoc or a blob: URL.

If you are in a Blink-based browser, you do have the ability to set the csp attribute and control what the embedded content can do on the network. It’s odd that this isn’t available on Gecko or WebKit-based browsers, as it seems like a very useful attribute to allow the host to have fine-grained control over what requests are allowed from the embedded frame.

If you want to run untrusted JS, you need to at least wrap the iframe in another iframe and process all the text to ensure that there are no other <iframe> elements in the input, and you have to ensure that they are on different origins (so don’t include sandbox='allow-same-origin').

The double iframe technique

There is a way to manage and control this, but I’ve not seen a huge amount of discussion about it online: the double iframe. This is a method used by a number of large-scale embedders (I believe Google Ads and OpenAI use it). The general concept is that you have an inner and an outer frame.

The outer iframe embeds a resource you control (often via srcdoc) and sets a restrictive policy on all network requests, acting as a policy firewall for the inner content:

<!-- Do not use this - You should sanitise srcdoc and likely set it via JS vs rendered from Server -->

<iframe

id="jail"

sandbox="allow-scripts"

srcdoc="

<!-- OUTER FRAME: Defines the 'No Network' Policy -->

<meta http-equiv='Content-Security-Policy' content='default-src "none"; script-src "unsafe-inline"; style-src "unsafe-inline"'>

<!-- INNER FRAME: Holds the content -->

<iframe sandbox='' srcdoc='

<h1>LLM Generated Content</h1>

<script>

// This fetch will fail immediately due to default-src 'none'

fetch('https://evil.com');

</script>

<img src='/someurlswithsecretdata'>

'></iframe>

"

></iframe>

The inner iframe will display the content and should have no ability to communicate with the host iframe. There are a number of issues with the above example:

- The very restrictive inner sandbox is isolated onto another origin and as such we can’t get access to the container size, so it’s hard to build good-looking UI. There might be a way to expand it to

allow-same-originbut you have to deal with the trade-offs. - This is still hard to manage. You have to ensure that the data included in the inner

srcdocis properly escaped so it doesn’t break out of the attribute string if you encode it straight from a server. - The double-iframe is also incredibly wasteful. It’s essentially loading two full DOMs (which are already heavy) every time we embed untrusted content.

Improving the iframe sandbox

The iframe is the only renderer sandbox we have, and I think there are a number of improvements browsers should make:

- All browsers should ship the

cspattribute and let the embedder refine and further restrict access to the network. - I’m not confident that CSP alone prevents all network access. The Beacon API might appear to queue a message. While

connect-srcshould strictly block beacons, edge cases in implementation can be tricky. Similarly, what happens with DNS lookups? A quick dump of the network traffic in Chrome viachrome://net-export/seems to show no network access, but I believe this area deserves more rigorous stress-testing. - We need a way to size the outer-iframe (or iframes in general) that doesn’t rely on access to

iframe.contentDocument.body.innerHeightandsandbox='allow-same-origin'. This constraint means that we have to fully untrust any JS that might be rendered in the inner-frame, and I think that is a shame because it would be nice to be able to have fully interactive experiences. - If we want to stream data into the iframe, we need

sandbox='allow-same-origin'which gives embedded content a way to access resources that are local to the current origin (cookies etc). It would be useful to be able to stream updates to the DOM and keep them on separate origins. - I would like a way to reduce the overhead of iframes. If we are disabling advanced functionality, do they get loaded in the DOM? I really don’t know about this, but having the double-iframe is doubly wasteful.

There are probably more things that are needed, and I don’t know if it will be easier to have something like a new dedicated element like <sandbox href> that is more suited to running untrusted content. Chrome did propose Fenced Frames for the Privacy Sandbox project that solves some of these issues. It allows for passing of data between frames in a controlled way and can entirely disable network access with disableUntrustedNetwork(). This doesn’t work outside of Chrome, so your options are limited.

The execution environment

We’ve somewhat locked down the network and we feel somewhat confident that we can constrain the content coming back from the LLM. We think we have a pretty reasonable set of sandboxing options for the file system. What about execution?

LLMs are incredibly powerful when they have access to tools. Many of these tools are now provided as MCP servers, which is out of scope for this post. The tools I am talking about are developer-provided functions that the LLM can determine which is best to call.

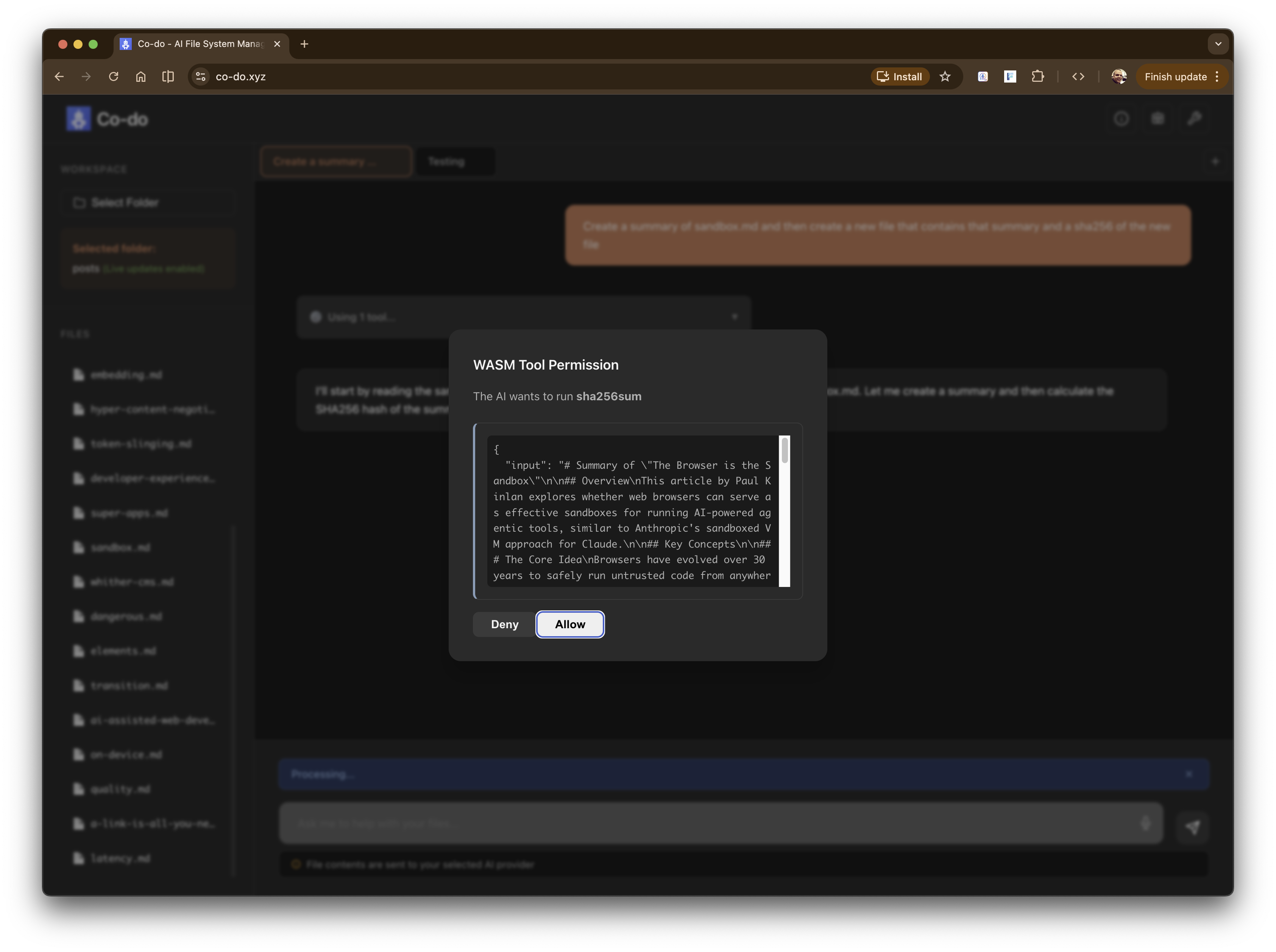

It turns out we have two runtimes in the browser that allow us to run code: the JS environment that we all know and love, and the WebAssembly (WASM) runtime. Both are designed to be able to run code from any untrusted source safely on the user’s computer. WASM in particular is incredibly interesting because it enables us to bring decades of software from other systems and run them safely inside the browser. For example, it’s possible to create and run a sqlite database entirely inside the browser by compiling it to WASM. The WASM security model is robust, designed specifically to execute untrusted binaries safely.

Running untrusted code directly in the DOM, or even running code we trust with untrusted input, is incredibly risky, so the execution needs to be further sandboxed as far away as possible from our UI environment. We could maybe think about running them in an iframe as noted above; however, Web Workers let us isolate our code from the UI in both the DOM manipulation sense and the off-the-main-thread sense. Web Workers can also inherit a very strict set of CSP constraints that block network access.

Putting it into practice: Co-do

So how feasible is this to put into practice? Well, I built a demo.

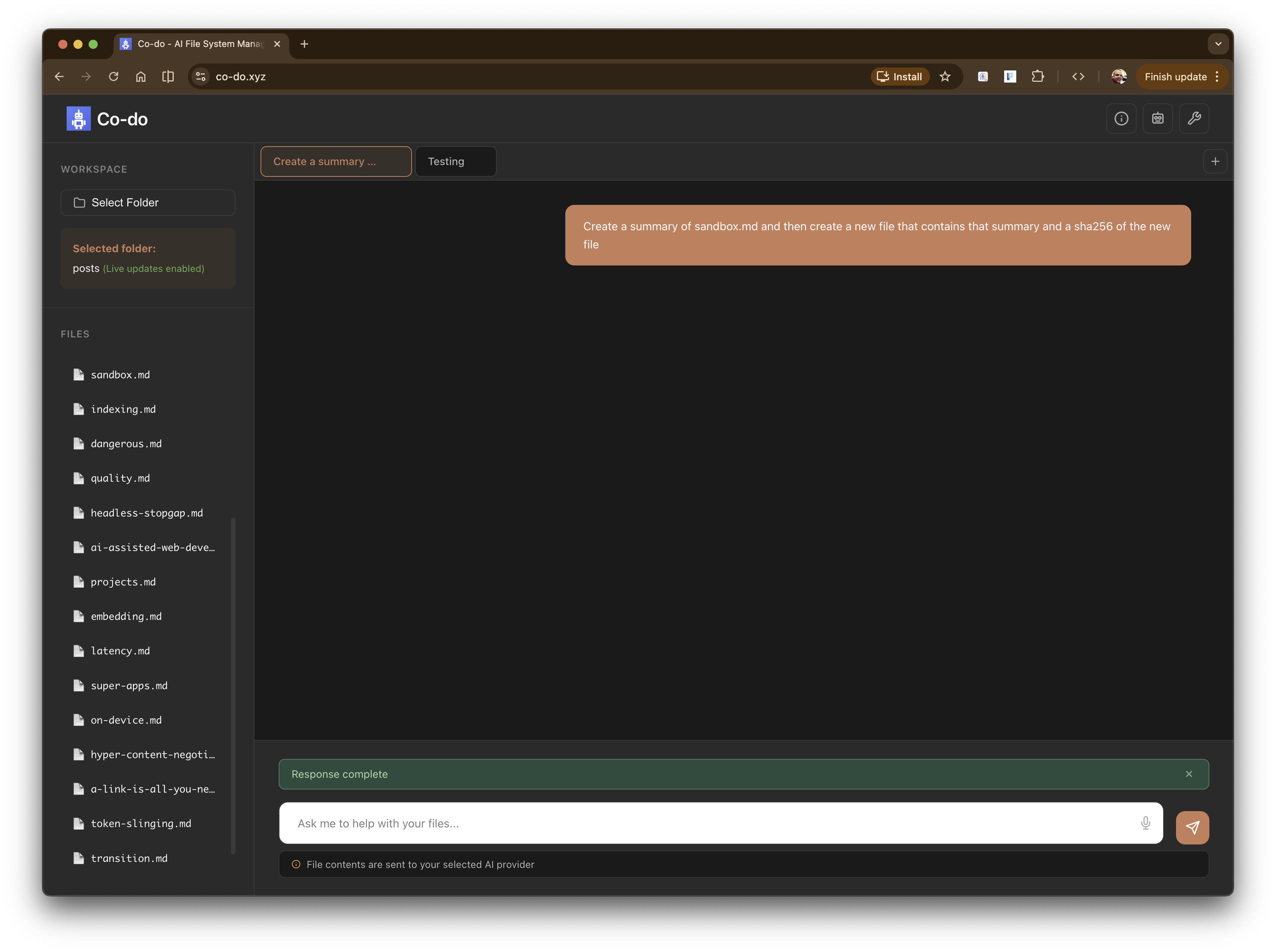

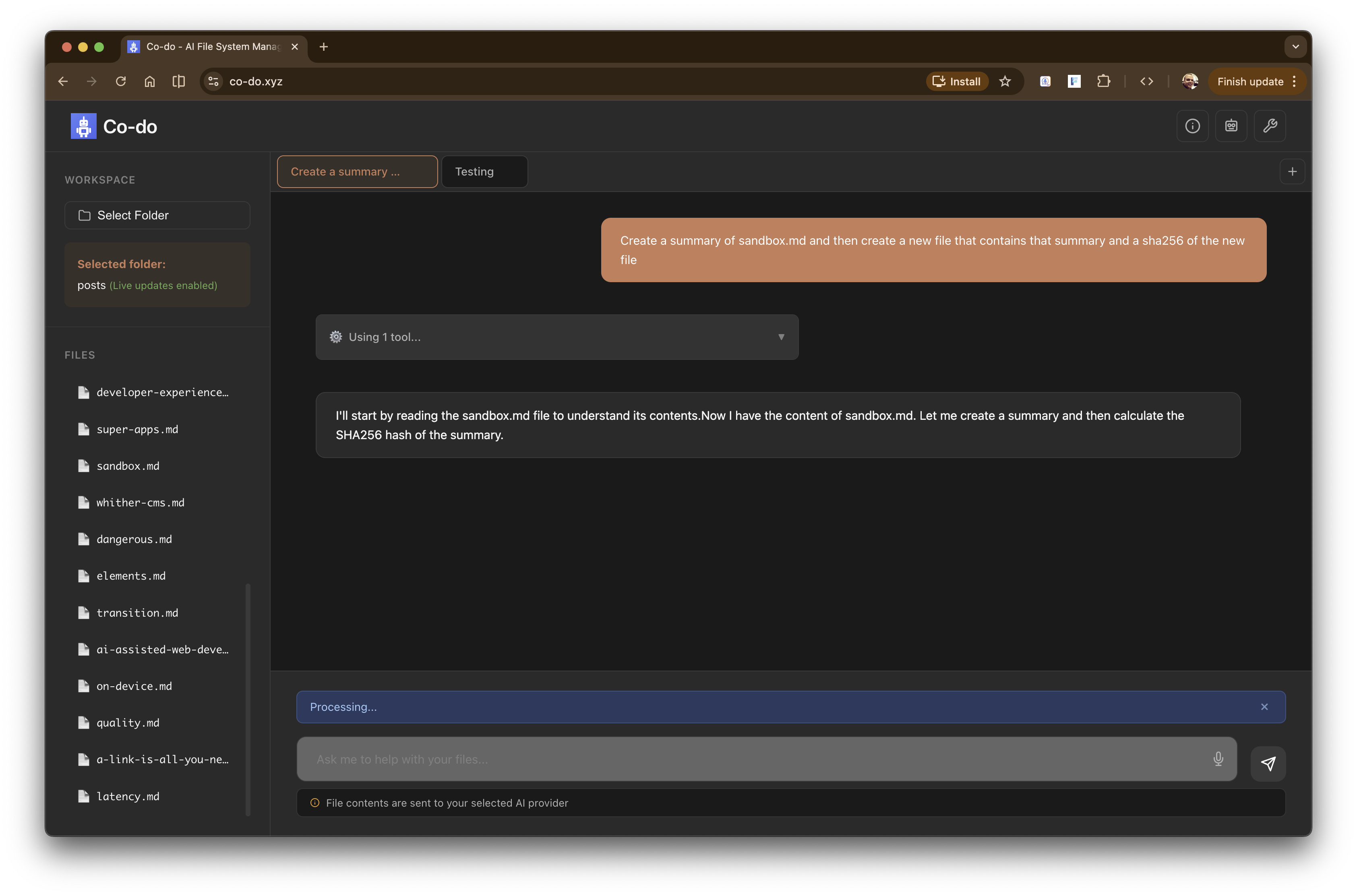

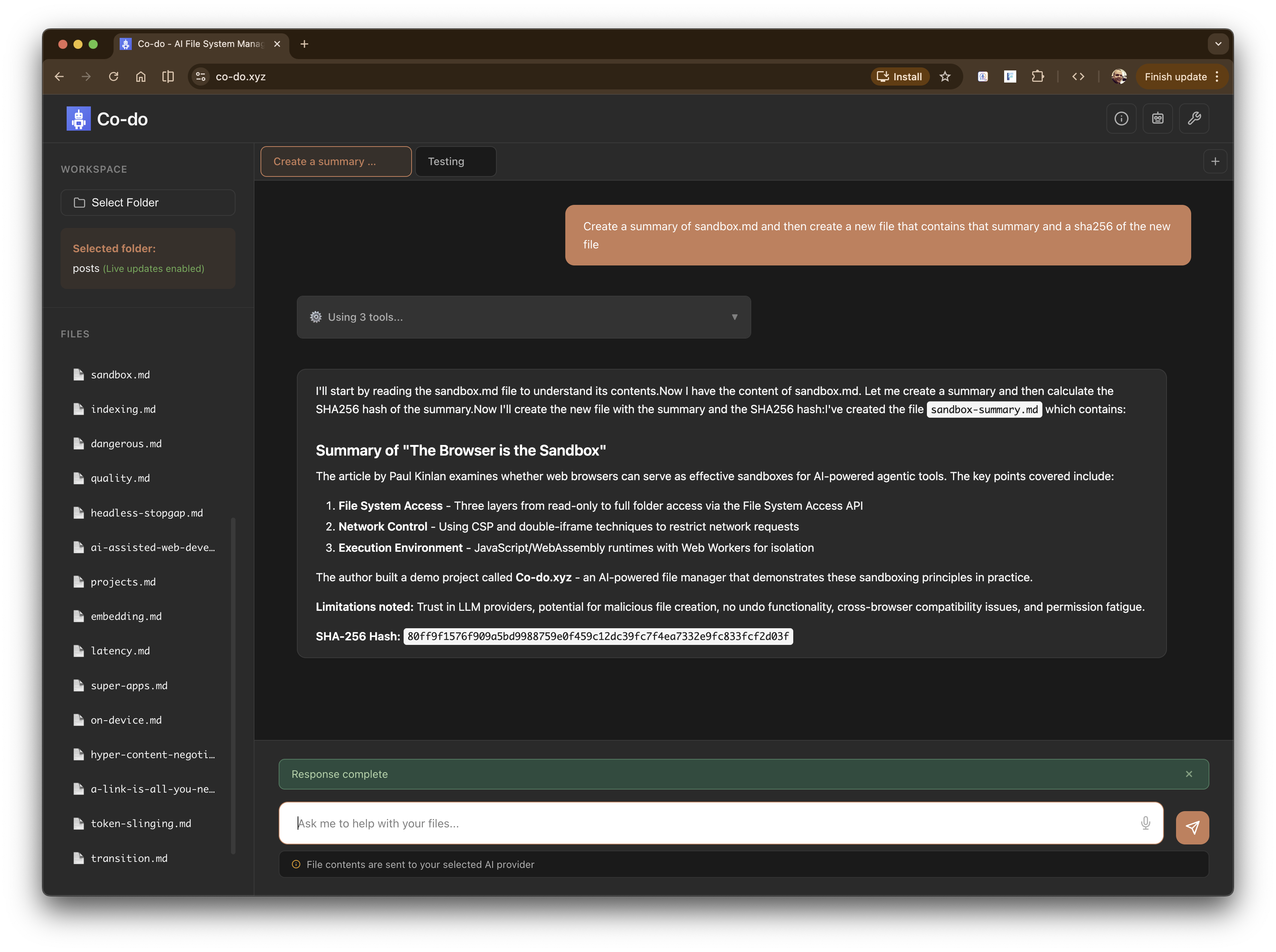

Introducing co-do.xyz [Source] - a demo and an experiment (with no warranties) of everything that we’ve talked about above.

Co-do is an AI-powered file manager that runs entirely in the browser. You grant it access to a folder on your machine, configure your AI provider (Anthropic, OpenAI, or Google), and ask it to help with file operations: listing files, creating documents, searching content, comparing files. It also has access to a number of pre-compiled WASM binaries for operations that you might want to perform on text files (for now, I’m hoping to bundle ffmpeg later).

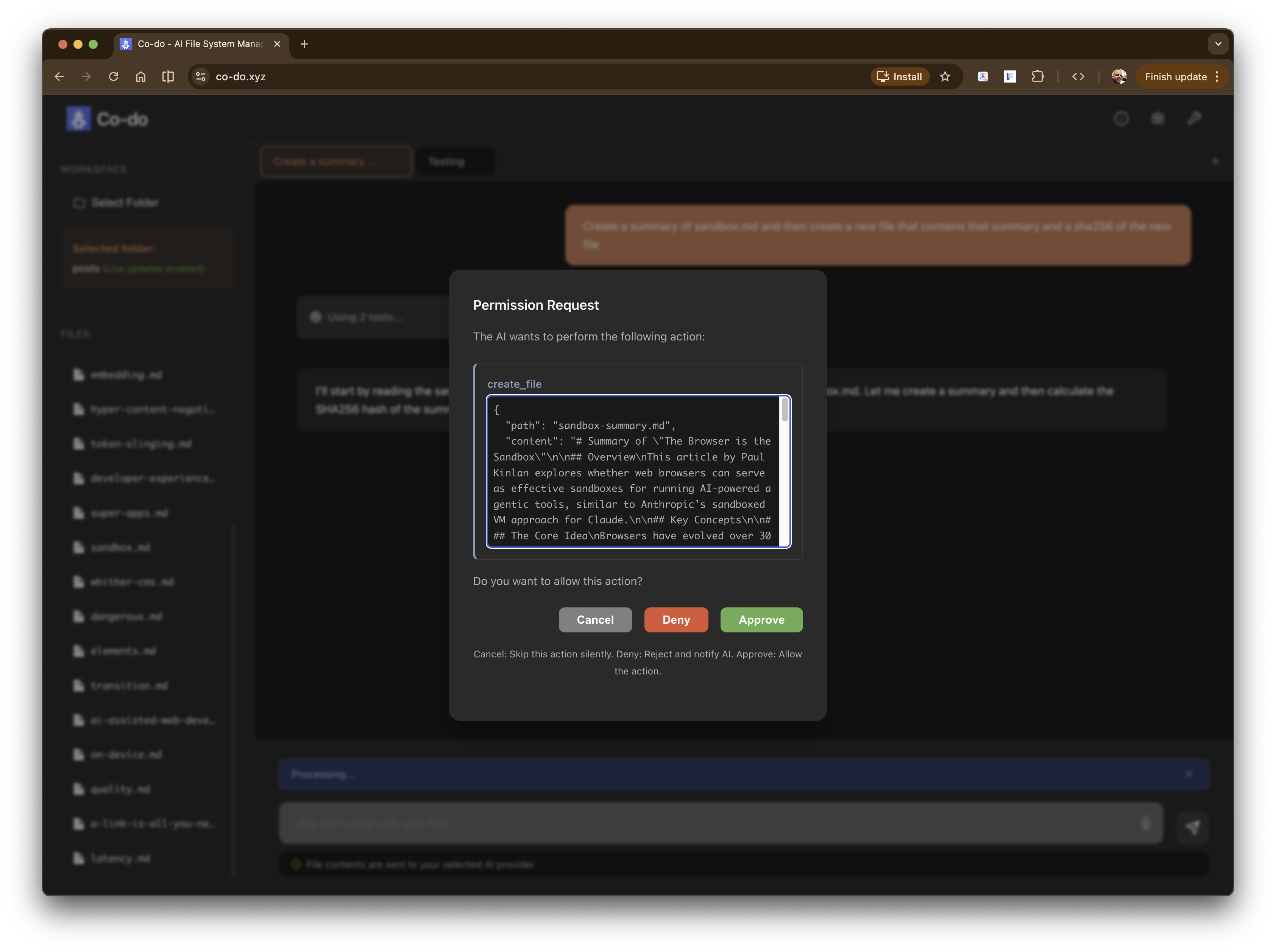

Co-do - asking a complex request on file data Co-do - planning Co-do - Using a WASM tool and asking for permission - sha256 - to hash a file Co-do - Asking for permission to create a file on the filesystem Co-do - All done - summary, new file and sha256

Here is the summary file that was created in the screenshots.

It implements the layered sandboxing approach we discussed:

- File system isolation via the File System Access API - You select a folder, and Co-do can only operate within that boundary. No reaching up to parent directories, no accessing siblings. It’s the browser’s chroot equivalent.

- Network lockdown via CSP - The strictest policy I could manage is to block everything and then only allow:

connect-src 'self' https://api.anthropic.com https://api.openai.com https://generativelanguage.googleapis.com. Only the AI providers can receive your data. Image tags exfiltrating content to unknown servers should not be easy, but there’s a world where any of these three API providers has an endpoint that could be accessible by a simpleGET. - LLM input guarding - The current demo will send the contents of the file to the LLM. Firstly, this might not be needed for tool calling, and secondly, you have to be confident that tools you configure on your call to the LLM won’t leak data (for example, many APIs have a Web Search tool - is it secure? I’m sure the providers do their best, but you need to make sure it’s not a new vector for exfiltration).

- LLM output sandboxing - AI responses render in sandboxed iframes with

allow-same-originbut critically notallow-scripts. The LLM can’t inject executable JavaScript into the page. We can measure the content height for proper display, but any<script>tags are dead on arrival. - Execution isolation for custom tools - Co-do supports WebAssembly custom tools that run in isolated Web Workers. Each execution gets a fresh Worker that can be truly terminated if it misbehaves (timeouts, runaway loops). The Workers inherit the CSP, so even WASM modules shouldn’t be able to make unauthorised network requests.

Known gaps

There are some gaps that everyone should be aware of:

- You’re still trusting the LLM provider. Your file contents get sent to Anthropic, OpenAI, or Google for processing. CSP ensures data only goes there, but “there” is still a third party. A fully local model would solve this, but we’re not quite there yet for capable models in the browser.

- Malicious file creation is still possible. The LLM could create a .docx with macros, a .bat file, or a malicious script that’s harmless in the browser but dangerous when opened by another application. The sandbox protects the browser session, not your whole system.

- The allow-same-origin trade-off. The markdown iframe needs this to calculate content height for proper display. This means I can’t run scripts and have same-origin access without the iframe being able to escape its sandbox. I chose no scripts, but it’s a compromise - I can’t offer interactive rendered content.

- CSP might not block everything. I’m reasonably confident about fetch and XHR, but what about the Beacon API queuing requests? DNS prefetch for resources? A

chrome://net-export/dump looked clean, but I don’t have complete certainty. More investigation needed. - No undo. If you grant write permission and the LLM deletes a file, it’s gone. Co-do has granular permissions (always allow, ask each time, never allow) but no backup system. The browser’s sandbox keeps the LLM in its lane, but within that lane, destructive operations are destructive.

- Permission fatigue is real. Asking users to approve every operation is secure but annoying. Letting users blanket-allow operations is convenient but risky. I’ve tried to find a middle ground, but the fundamental tension remains.

- Cross-browser limitations. The

cspattribute on iframes only works in Blink-based browsers. The double-iframe technique works everywhere but it’s wasteful and awkward. Safari’s File System Access API support is limited (specifically, it lacksshowDirectoryPicker, making the local folder editing workflow impossible currently).

This is really a Chrome demo.

Is it perfect? No. But I think it demonstrates that the browser’s 30-year-old security model, built for running hostile code from strangers the moment you click a link, might be better suited for agentic AI than we give it credit for. However, I do think there should be a lot more investment from browser vendors in improving the primitives for securely running generated content (be it an ad, an LLM, or any embed).